Into the Labyrinth

A retrospective essay on hosting a labyrinth walk at a South Korean high school

A Note Before We Begin

This is a reflection on the labyrinth walk hosted at Gwacheon Foreign Language High School on 20 May 2025. Thank you to Mr. Thomas Hackney for auditing the class and offering feedback on my presentation, facilitation, and planning. Thank you as well to Mr. Park Jinseong for photographing the event with care for student privacy, and for the beautiful images included here. (You can find more of his work on his website.) Finally, thank you to my students for permission to share their anonymous reflections with Substack readers and the Veriditas Certification Committee.

The Bell

The bell at my school in South Korea is not the overenthusiastic clanging of hammers striking tiny gongs. No. It’s a soulless digital tune in D major, piped through crackling ceiling speakers.

This synthetic horror plays at the beginning and end of every period. It causes what little free time the students (and staff) manage to salvage between classes to evaporate on contact—and, just as reliably, detonates a teacher’s last, hopeful sentence halfway through its own existence. One moment you’re trying to land one final thought with dignity. The next, the melody arrives like an oddly cheerful demolition crew, and the students surge towards the door.

At 15:50, though, it hits with all the exuberant enthusiasm of the final bars of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 overture1. Same tune, same distorted buzz—but, this time, it marks the end of the formal school day (if not the end of the students’ time at school).

Tuesday, 20 May 2025, 15:50—that bell rang. The final English class of the day concluded, I made my way back to the foreign languages office, walking past classroom doors held open while desks were shunted aside to make room for sweeping and mopping. Inside, students sorted and carried out the day’s recycling and trash. Another group—armed with wet cloths and the brisk seriousness that comes from knowing you’ve only got a twenty-minute break—wiped down surfaces.

Blink and you’ll miss it. The entire affair takes less than five minutes.

If you’ve never spent time in a Korean school, this is one of the small cultural revelations that sneaks up on you. There’s no invisible army of caretakers arriving after hours to reset the building. The students do it with dignity and the understanding that it is in these rooms that their future is being formed.

I watched from my office as the last motions of cleaning resolved into stillness. And then—all at once—the exodus began.

A sudden Brownian motion: teenage bodies diffusing from classrooms into the openness of corridors and stairwells, and finally out into the playground. Ahead of them lay twenty minutes of open space and evening air before the extra-curricular program began.

Most would soon be heading back into classrooms filled with maths problems, video lectures on how to solve the notorious CSAT (수능/SuNeung) English questions, and the golden late-spring sun filtering through the blinds.

But for a small group of students, the evening held something else in store.

Our classes run from 16:10 to 17:00. That evening, as part of my course Folklore, Mythology and Me, I had arranged something that would bend the schedule. We’d meet in our usual time slot and dinner would follow, as usual, from 17:00–18:00.

From 18:00–19:00—after protracted negotiations with department heads, homeroom teachers, the sports department (who maintain a kind of permanent claim on the auditorium, except during the annual cultural festival), and the administration office—I’d managed to secure permission for any student who wanted to attend a labyrinth walk to be excused from supervised study for an additional hour. Instead of returning to their desks after dinner, they would come with me to the auditorium, where the labyrinth would be waiting.

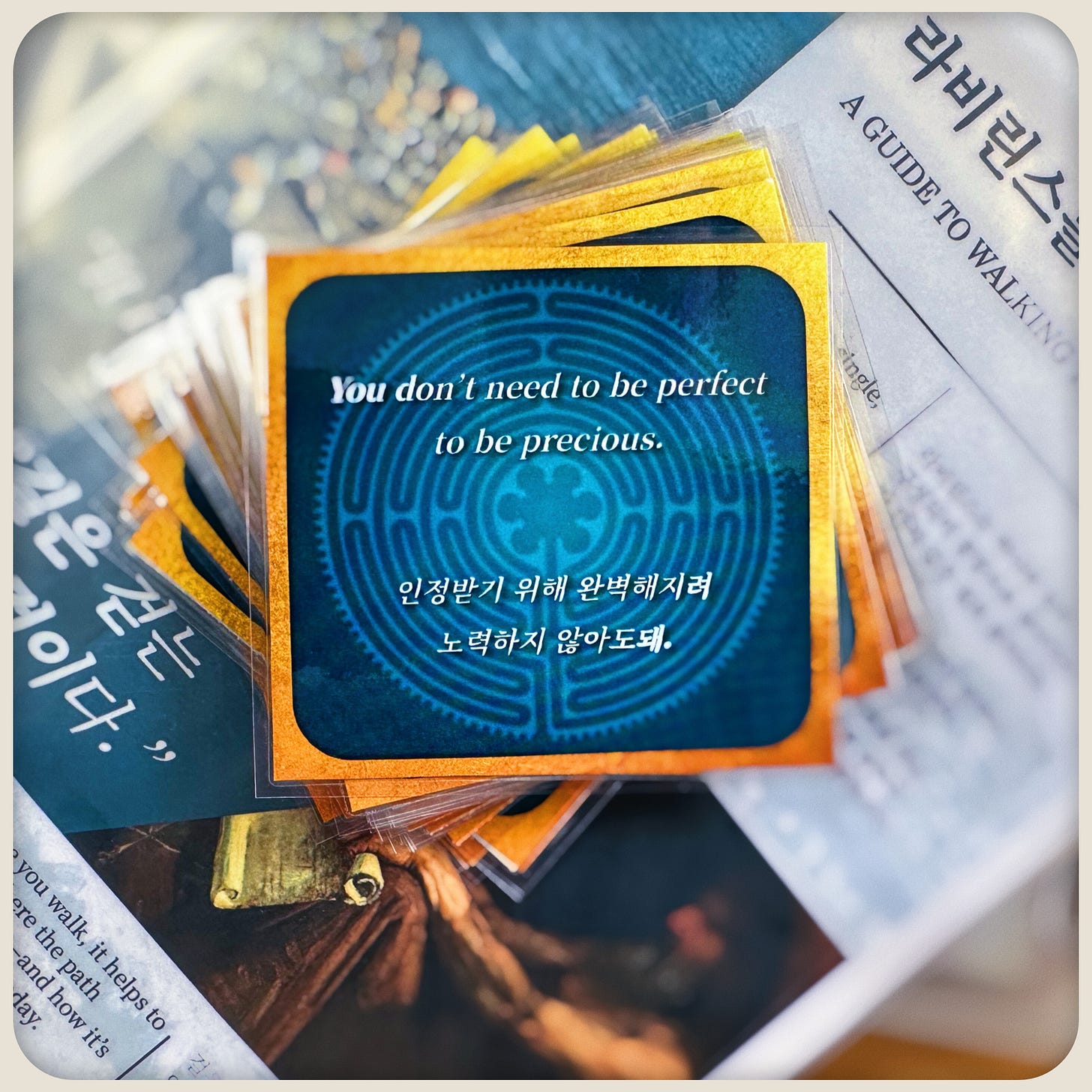

Tonight’s Lesson would mark the moment we moved from story and symbol into something riskier and more adult: the turning of insight into embodied practice. The heart of the evening would be a simple exchange. Each student would receive a carefully crafted message of affirmation on a small card—words that, in the pressure-cooker atmosphere of South Korean high school life, people don’t always get to hear out loud. They would sit with the message, meet their reaction to it, and then choose the moment to let it go—trading something that (I hoped) felt precious for a blank sheet of coloured paper on which they would write a message of their own.

For the students heading to my strangely unacademic course, the evening held what I hoped was the quiet thrill of something entirely different—something mythological that wouldn’t just be discussed, but walked.

The Road to the Labyrinth

By that point in the semester, we’d already been walking a winding path of thematically interrelated stories.

We’d begun with a Korean folktale about a bag of forgotten stories hung behind a kitchen door—and the trouble they caused when they slipped back into the world. We’d traced the long tension between mythos and logos, and asked what happens when imagination gets exiled from a culture. We’d sat with The Shipwrecked Sailor from Middle Kingdom Egypt, and followed the Perceval’s quest for the Grail into the bleak question the Fisher King was never asked. We’d returned to Crete and the palace at Knossos—and finally to the central story: King Minos and the Bull from the Sea.

This class mattered to me. It was the first full labyrinth walk I hosted after completing facilitator training with Veriditas—my first time using a labyrinth large enough to walk with the body, not just trace with a fingertip.

But before that, there was still one more classroom lesson to teach.

Session One: The Classroom

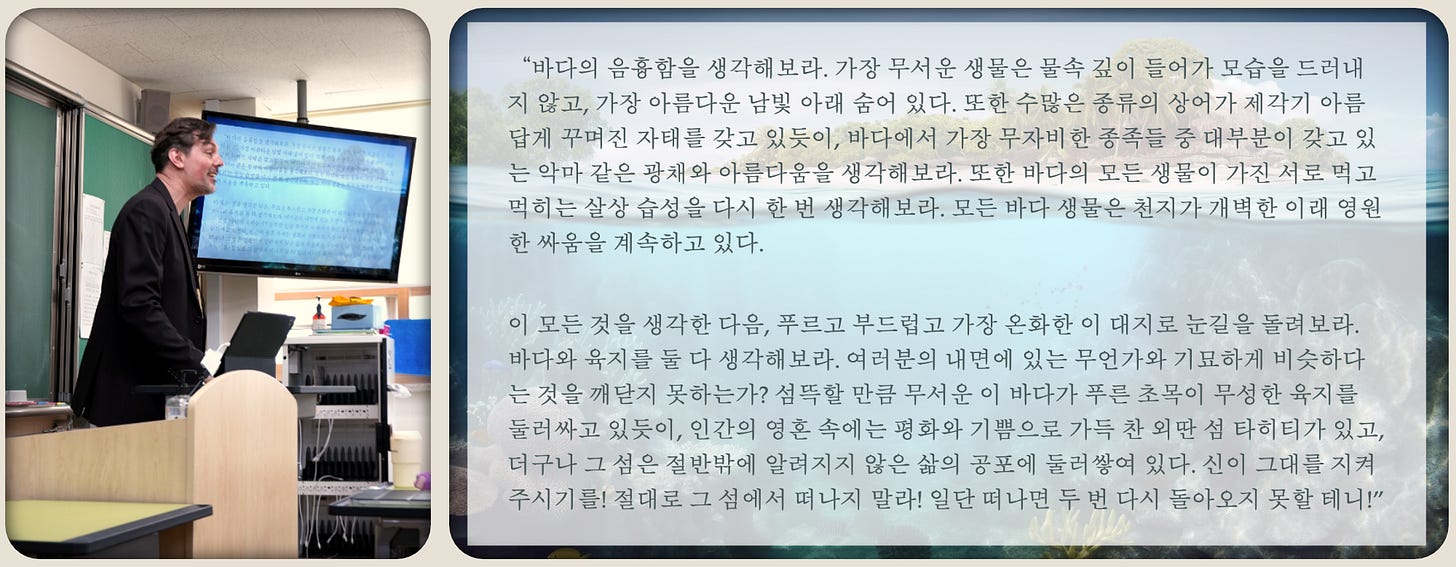

I began the class by putting Herman Melville on the screen in Korean—an old voice, strangely fresh in Korean script on the screen.

In Chapter 58 of Moby-Dick, he asks us to consider the sea: how the most dreaded creatures glide beneath the surface, mostly hidden, sometimes dazzling, and how the ocean’s beauty can be inseparable from its violence. Then he guides our attention towards the land and sea—and asks whether we recognise that strange analogy to something in ourselves. Each of us, he suggests, contains an “insular Tahiti”: a pocket of peace surrounded by half-known life. And he closes with an ominous benediction: “God keep thee—push not off from that isle, thou canst never return.”

I didn’t ask the students to analyse the passage in the usual academic way. I asked them to notice what it did to their imaginations.

The sea: beautiful, vast, and bright—and not particularly interested in your survival.

The land: familiar, orderly, and—at least on the surface—manageable.

Melville’s question hung in the air on that day as it does now. Do you recognise the analogy?

After a moment of calm reflection, we hoisted sail and caught the wind of an all too familiar story: the myth of King Minos and Bull from the Sea.

The Bull and the Burnout

This is an annotated and (slightly) expanded transcript of episode 2 of my podcast where we explore the intersection of mythology, folklore, and modern life. I'm Dimitri, and I'll be your companion on this journey of discovery.

By Lesson 8 we’d already spent quite a bit of time at Knossos, talking about the danger of inflation—what happens when a person (or a ruler) starts believing too completely in their own story. Minos is the patron saint of Believing Your Own Press. He receives a magnificent white bull as a sign of status and favour, and becomes so attached to what it seems to prove about him that he can’t let it go. In the end, he builds a labyrinth—not as a marvel of architecture, but as a hiding place for the consequences of his grip.

The parallel with Melville’s Captain Ahab is striking. Both are obsessed. And obsession, once it takes hold, has a way of narrowing the world until a single object—a bull, a whale, a grudge, a goal—starts to feel like destiny itself. Ahab cannot leave off his chase of the white whale any more than Minos can relinquish his claim on that magnificent bull.

And here, too, was Melville’s analogy—closer than it first appears. These stories show what happens when we start building a self around a fixation; when one story becomes the hub around which everything else is organised. Something that should have been met, recognised—and released instead becomes a life’s centre of gravity.

But seeing that pattern echoed across thousands of years isn’t the end of the work. Knowing things—recognising motifs, naming symbols, making clever connections—can genuinely help. It can also become a kind of safe entertainment: insight that never has to risk anything.

The more important step—the one that actually changes a life—is that of embodiment: when understanding begins showing up in action. Insight and knowledge are not enough. For them to truly be valuable, they have to show up in what we do, in what we avoid, in what we practise—in what we repeatedly choose.

So I gave them an example from my own life, one without the mythic grandeur attached to it: my long-standing claim that I was “bad at maths.”

For years that sentence felt like a biological certainty, as if somewhere deep in my DNA there was a gene that simply barred me from numbers. But it wasn’t a fact. It was a story—one that shut down possibility and protected me from the humiliation of trying. Later, when I finally had a patient teacher (my grandfather), and when I applied myself with even a little consistency, the “truth” shifted. I went from an F to a high B. Nothing about me as a person had changed. But the story I told myself had—and because the story changed, my actions changed.

“I’m bad at maths” sounds like a statement about reality. A more honest version might be: “I dislike maths because I don’t understand it yet—and I haven’t properly tried to fix what I don’t understand.” The same life, told one way, is a prison. Told the other way, it’s a doorway.

I asked the students to take a few minutes to journal about a story they might be mistaking for truth—something they say about themselves with the same concrete certainty: I can’t do this. I’m not that kind of person. I always fail at that. I hate speaking in public. I’m just not confident.

Because this is where the myths stop being “about” Minos or Ahab and start becoming relevant to the ordinary, modern lives sitting in front of me. The thing that rises up from somewhere half-known inside us—the thought we accept without question, the fixation we keep feeding, the fear we keep rehearsing—can end up steering far more than we realise.

We ended by going over the labyrinth walk procedure: what would happen after dinner, how the space would work, what was expected (very little), and what wasn’t (performance, or the need to do it the “right” way, or have the “proper” experience). Then class was over—the awful song played again—and the students went to eat.

And while they ate, I headed for the auditorium.

Interlude: Dinner and Setup

While the students headed toward dinner, I went the other way—down quiet corridors and up deserted flights of stairs to the auditorium—carrying the unmistakable mix of anticipation and logistical dread that should rightfully accompany any “transformative experience” that depends on tape, a tarp, and the cooperation of institutional furniture. Was the tape still sticking to the tarp? Would I walk in and find five hundred chairs set up in neat rows?

The school’s auditorium not a sacred space. It’s a practical one. Teenagers know what it’s for: sports, announcements, an annual cultural showcase, and the collective endurance of required for when some adult speaks for far too long. It is certainly not a place in which one usually takes meandering, reflective walks.

Which is why the task—before any labyrinth could appear—was to negotiate with the room’s default identity.

The badminton nets were up, pulled taut across the floor like territorial declarations from the sports department. And like many high school sports departments, the equipment didn’t politely move aside when asked. It had to be dragged. Wheels that promised ease delivered the kind of irony only English departments would appreciate2. Nothing about it was poetic. And yet there I was, hauling those bulky frames toward the edges, trying not to scratch the floor or tangle the nets lest I be barred from using the venue ever again.

Then came the tarp.

A ten-by-ten metres does not unfold like a picnic blanket. At first, it is just a stubborn mass. I wrestled it open, smoothed it where I could, and nudged the edges into place.

In the empty hall, the ancient pattern incongruously rendered in tape on beige waterproof fabric looked strange. The two lights I had turned on reflected off the creases in the tarp—a still life of the surface of the sea.

I completed my preparations in a few steps: the speaker and iPad for the ocean soundscape; the box that would wait at the center; the cards, the papers, the markers. I left a few final pieces for the students to do when they arrived. Partly because it saves time. Partly because it changes the atmosphere. If they help build the space, even in small ways, they enter it differently.

I tested the sound. The gentle rhythm of surf and gulls filled the hall.

Then I waited.

By 17:50, the doors opened and the first few arrived. They came in clusters—some still sipping drinks from the snack shop, some checking phones. But as they walked in, the energy shifted and they grew suddenly quiet as they took in the labyrinth. Their presence was the final piece in the setting of the venue. The transformation was complete and the auditorium took on the atmosphere of a sanctuary.

And whatever we were doing—whether quietly taking in the scene, sitting on the floor, or, like me, feeling a little worried and waiting to see who would show up—our walks had already begun.

Session Two: Into the Labyrinth

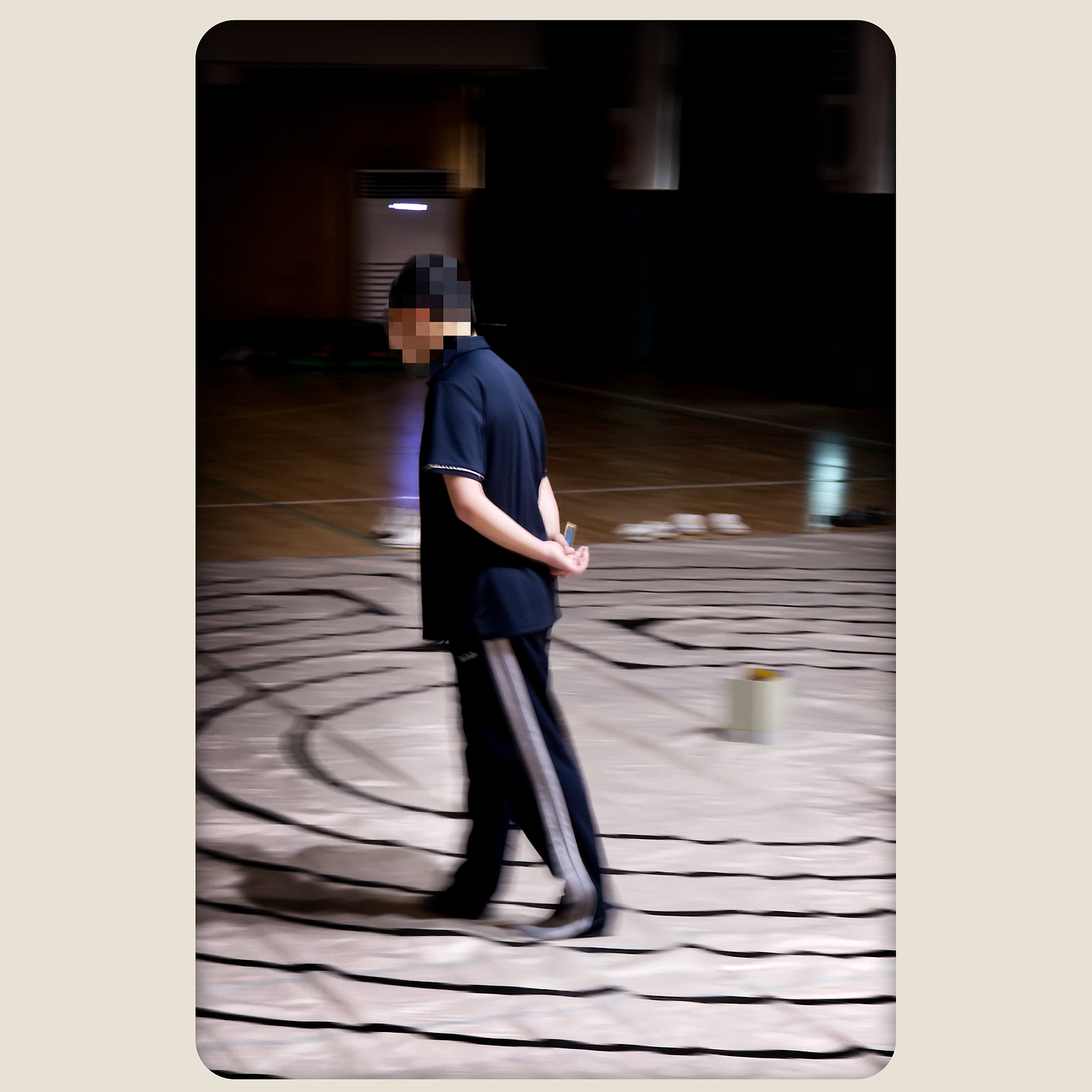

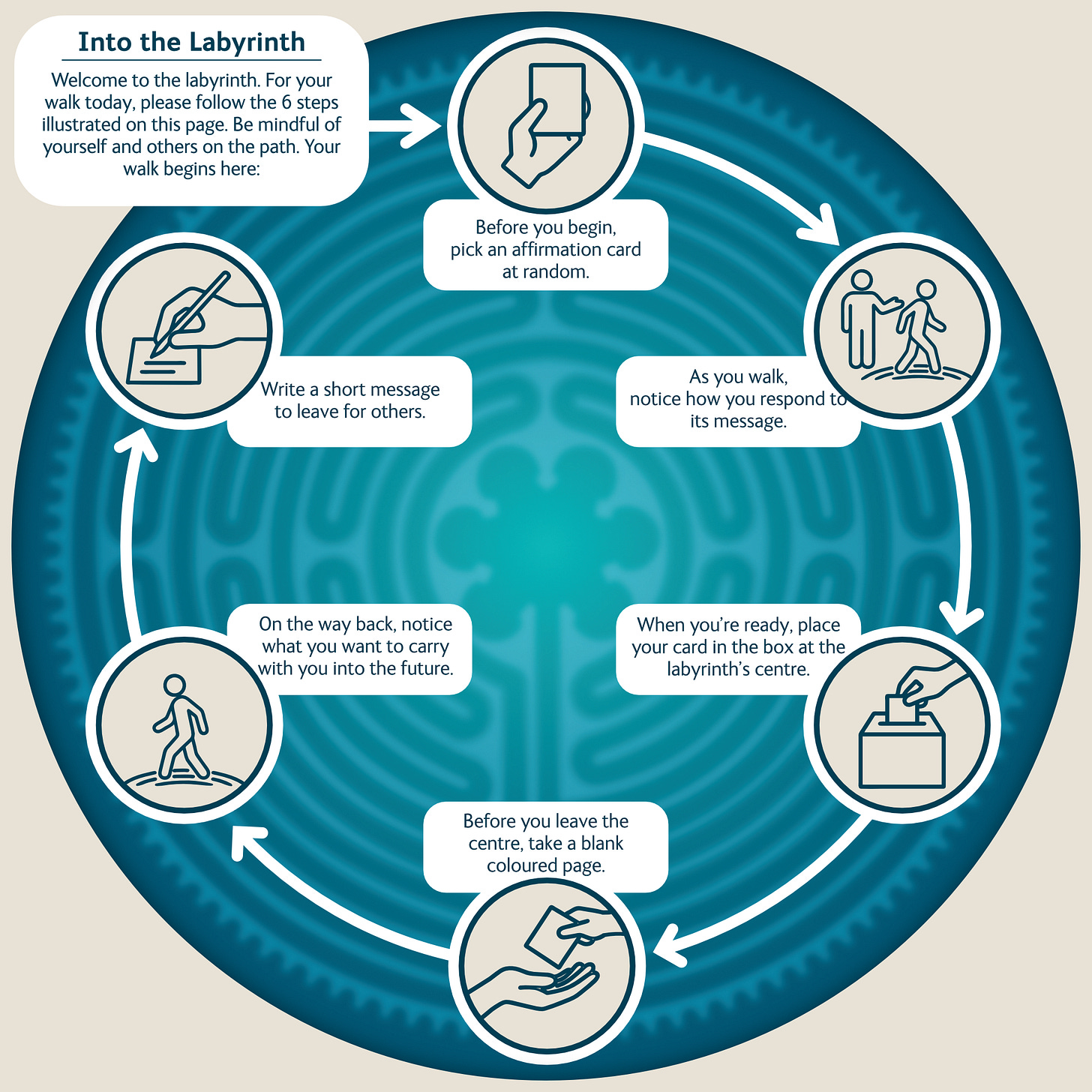

At 18:00 that bell rang again. By now, all 20 of the students registered in my course had arrived and we began the second session by warming the space. I reminded them of the procedure we had discussed: first, we would walk the outside of the labyrinth—letting our bodies learn its shape before we tried to enter it.

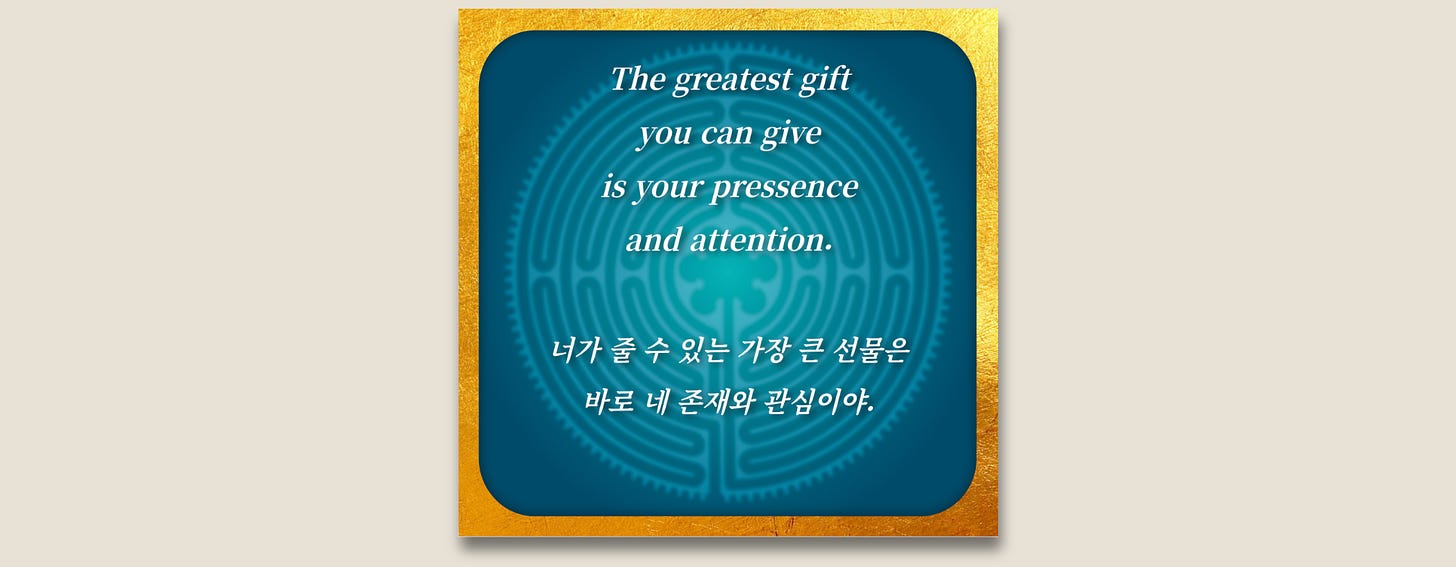

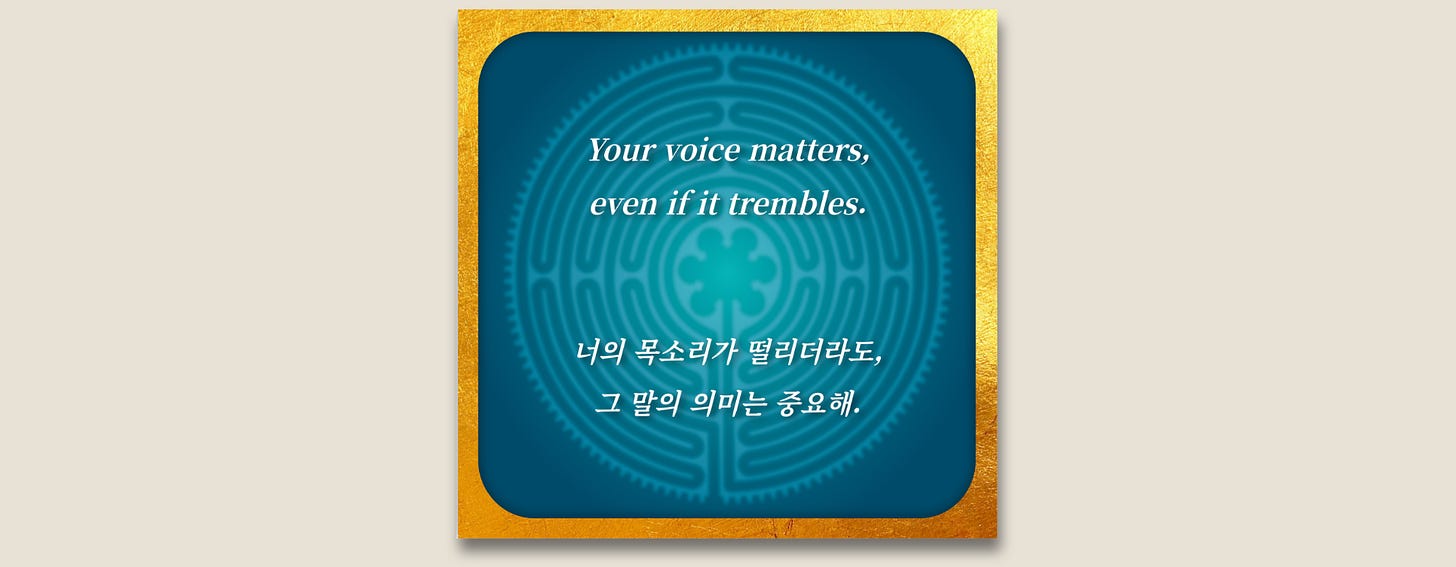

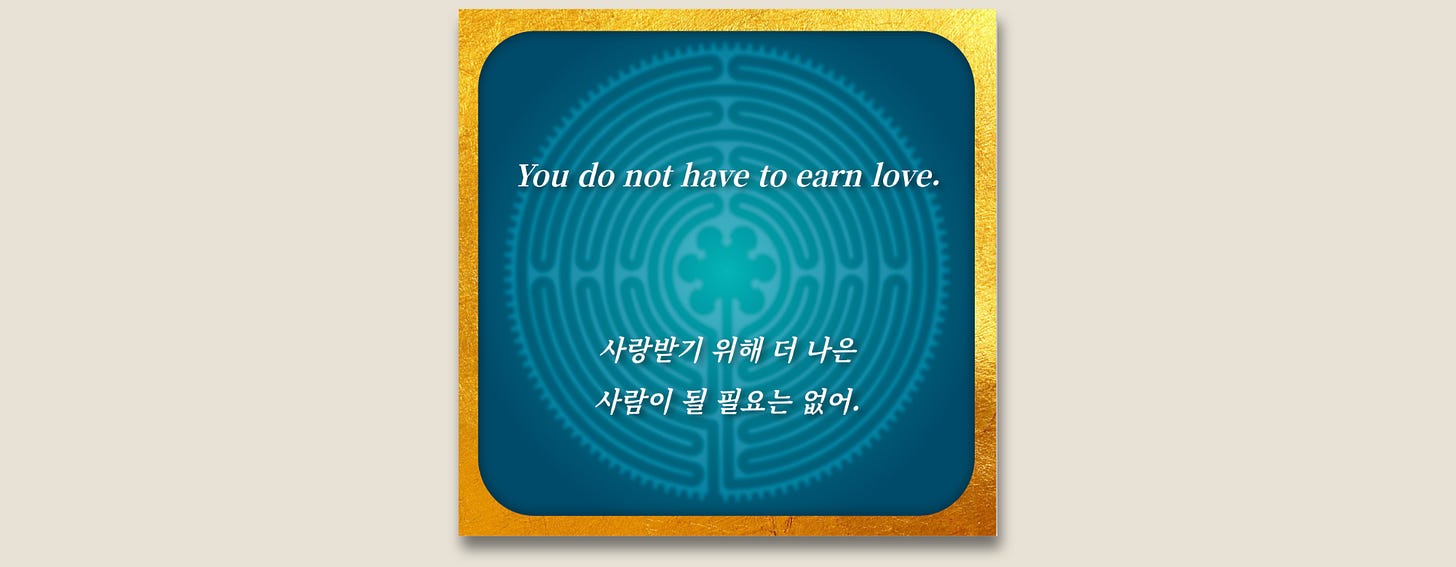

On that first circuit, each student would take a single affirmation card at random—no hunting for the “best” one, no swapping with friends, no treating it like fortune-telling. Just one card. One message. Something to be read and, for the duration of the walk, received as meant for them. Something to hold lightly.

They could circle the perimeter as many times as they needed. Then—if and when they felt ready—they could come to me at the entrance. I would space the walkers out so no one felt chased, and so the path stayed open enough for each person to have their own experience without feeling that anyone was pressing too close behind.

We began.

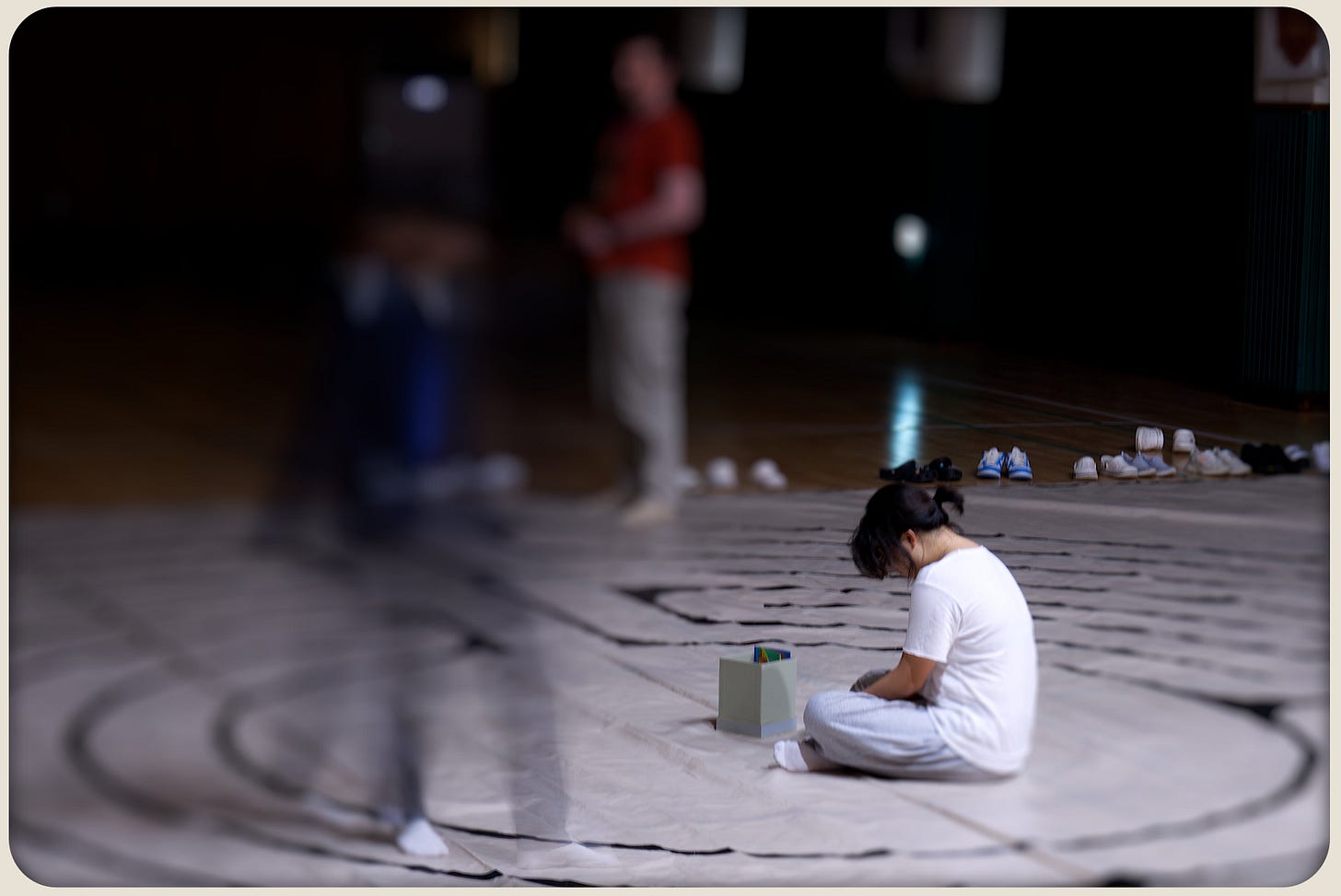

They moved around the outer ring in a loose orbit: ocean sound in the air, the soft drag and whisper of tarp underfoot, the taped lines glinting as they caught the light. On that first loop, hands reached for cards. Some students glanced down immediately. Some held the card at their side, as if they didn’t want to be seen reading it. Some read, then folded it inward quickly, as if it had suddenly become something intensely private.

A few accepted the words on their card easily. Quite a few didn’t or couldn’t. Their resistance showed on their faces and in their walk. But as they continued around the perimeter, something started to change.

And then, one by one, they approached the entrance.

Not in a line—thankfully not—though a few clearly wanted to go in pairs. For the sake of the space, I quietly separated them, letting friends walk in the same general window but reminding them of the one expectation that mattered: the labyrinth is a path each person walks by—and for—themselves. Some began winding their way towards the center while others seemed to be content walking around the outside. Each was fully engaged in a dialogue with something inside themselves.

At the entrance, each student waited, watched the person ahead make that first turn, then stepped forward when I indicated that there was space enough for them to begin. After a few had entered, it became quite apparent that the labyrinth taught its own etiquette without me needing to put it into words. You share one path. You don’t rush. You don’t perform. You just walk.

By the time most of the students had crossed the threshold and had begun moving inward, the auditorium felt like a completely different place. The gym had stopped being a gym. The room had become quiet in a way schools rarely are: not “teacher is watching” quiet, not disciplined quiet—just quiet, because something honest was happening.

The labyrinth—taped lines on a beige tarp—was doing its work.

The Center: Learning to Let Go

The center of a labyrinth looks like a destination. Even if you’ve listened to a teacher or facilitator go on about it for a while—it’s difficult not to feel that reaching the center is a moment of achievement: the point at which you’ve reached the goal of your walk.

It’s only once you’re standing there that you realise it’s really just a pause. What you mistook for the goal is actually a container—a vessel in which abstract insights are transmuted into physical experience.

When a student reached the middle, they were invited to sit—if they wanted—and stay as long as they needed. Some folded down immediately. Some hovered, uncertain, as if waiting for the next instruction. A few simply stood there, holding their card with both hands, letting the message settle.

Each knew this would be the last time they ever held that particular card. The last time those words would exist in their hands in that form. No matter how precious receiving the message might have felt, it was never meant to become a talisman. It was meant to be received—and then released.

The cards were written as messages from me to them: teacher to student, human to human. I’d tried to craft each one so it could be true for anyone in the room—simple statements about experiences common to all people, but specific enough to feel personal. And the moment a message like that lands in your hand, the mind does what it always does:

Yes, but…

That may be true for others, but it can’t be about me.

I don’t deserve that.

I’m not like that.

These words aren’t for me.

That friction was part of the point. The cards were there to bring a familiar resistance into view: the reflex to reject a kinder story about yourself than the one you’ve rehearsed for years. To lure those quiet, unquestioned beliefs—I’m bad at maths. I’m not confident. I can’t do that—into the light long enough to look at them, and then, like the card, loosen your grip.

When they felt ready, each student placed their affirmation card in a box in the center of the labyrinth.

And then—only then—they took something else in its place: a single sheet of coloured paper.

It was a small exchange, almost laughably simple. A piece of cardstock for a piece of cardstock. But hidden inside that tiny action was the core moment of embodied insight.

The affirmation card was designed to feel precious. I told them—explicitly—that this would be the last time they ever held that particular message in their hands. Scarcity does what scarcity always does: it makes paper feel like treasure.

The coloured page, on the other hand, was blank. It held no message. No reassurance. No proof that it had been “meant” for them. Just an empty surface whose value would be determined by the choices they made.

In the comfortable lighting of the auditorium, accompanied by the strangely complimentary blend of recorded ocean-scape and the sounds of socks shushing and scrunching over the creases in the PVC tarp, students encountered that moment on their own terms. No one took their card away. No bell rang to announce time’s up. Each student had to choose the moment to let go. They had to decide when they’d allowed my words to define their experience long enough—and when it was time to release them into the box and take up something riskier: the responsibility of their potential embodied in that blank page.

In a way, it echoed the stories we’d been circling for weeks. Minos could not let go of the bull he mistook for proof of who he was. Ahab could not release the definition his wound stamped into his being. Both men clung to an external message until it swallowed everything.

The labyrinth offered my students a gentler, smaller version of that same crossroads: here is a message. Here is the temptation to clutch it. And here is the invitation to put it down—and step into authorship.

One by one, cards disappeared into the box. Some students did it quickly, like ripping off a bandage. Some did it slowly, with tears and careful tenderness. And then they rose, holding their coloured page, and began the walk outward—back through the turns, back toward the entrance, back toward the world.

The Way Back and the Marks We Leave

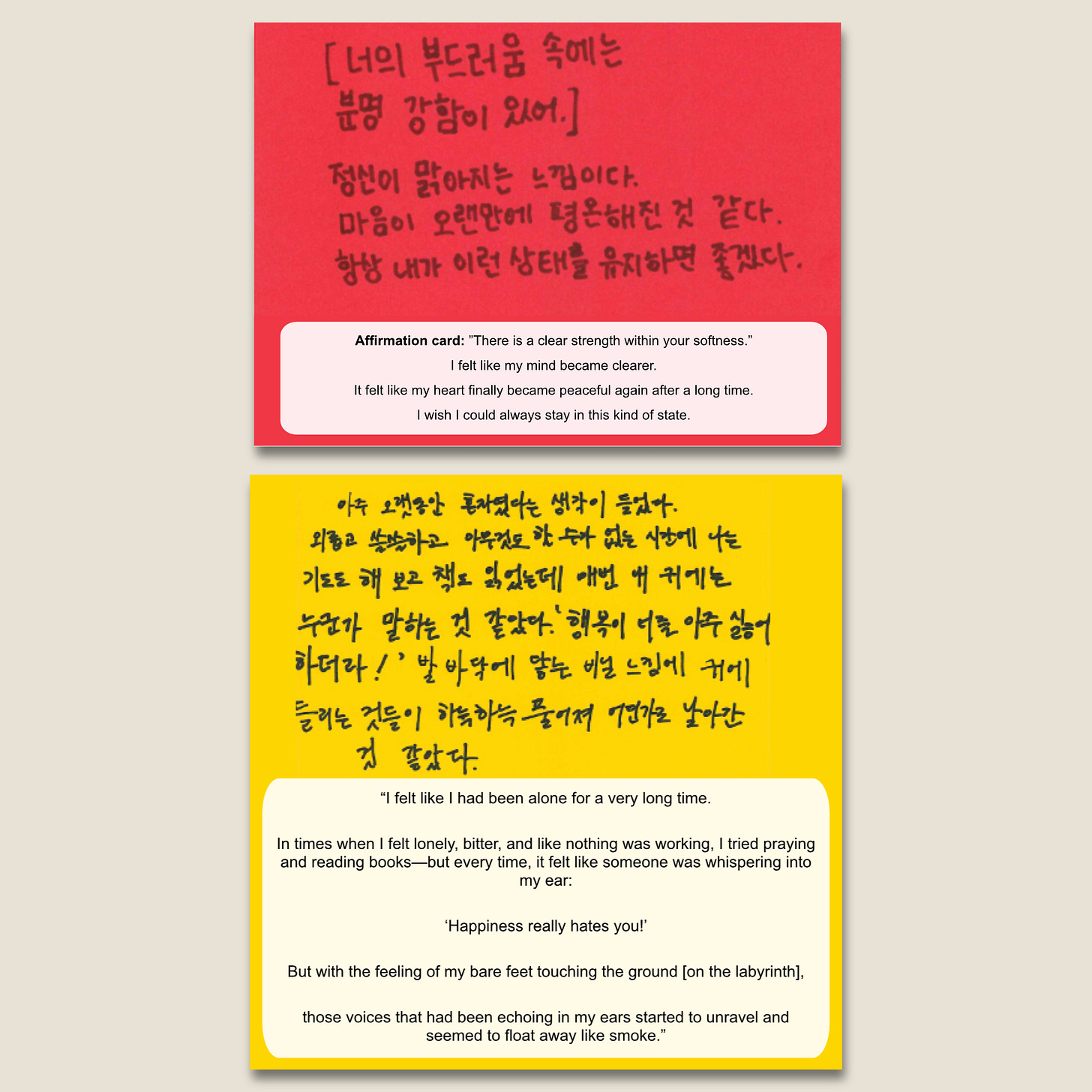

A labyrinth is unicursal: there is only one way in, and it’s the same one as the way out. There are no dead ends, no puzzles to solve—and yet the way out never feels the same as the way in. The turns that carried the students inward now carried them back toward the edge, coloured page in hand, the ocean sound still washing through the room.

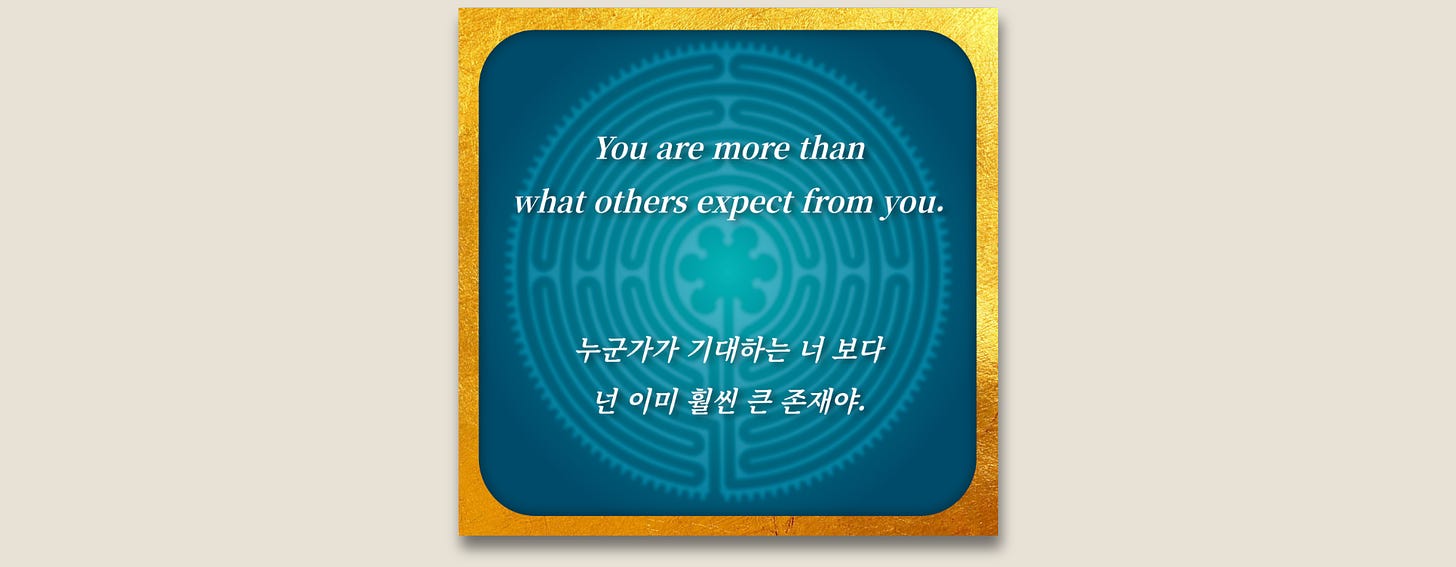

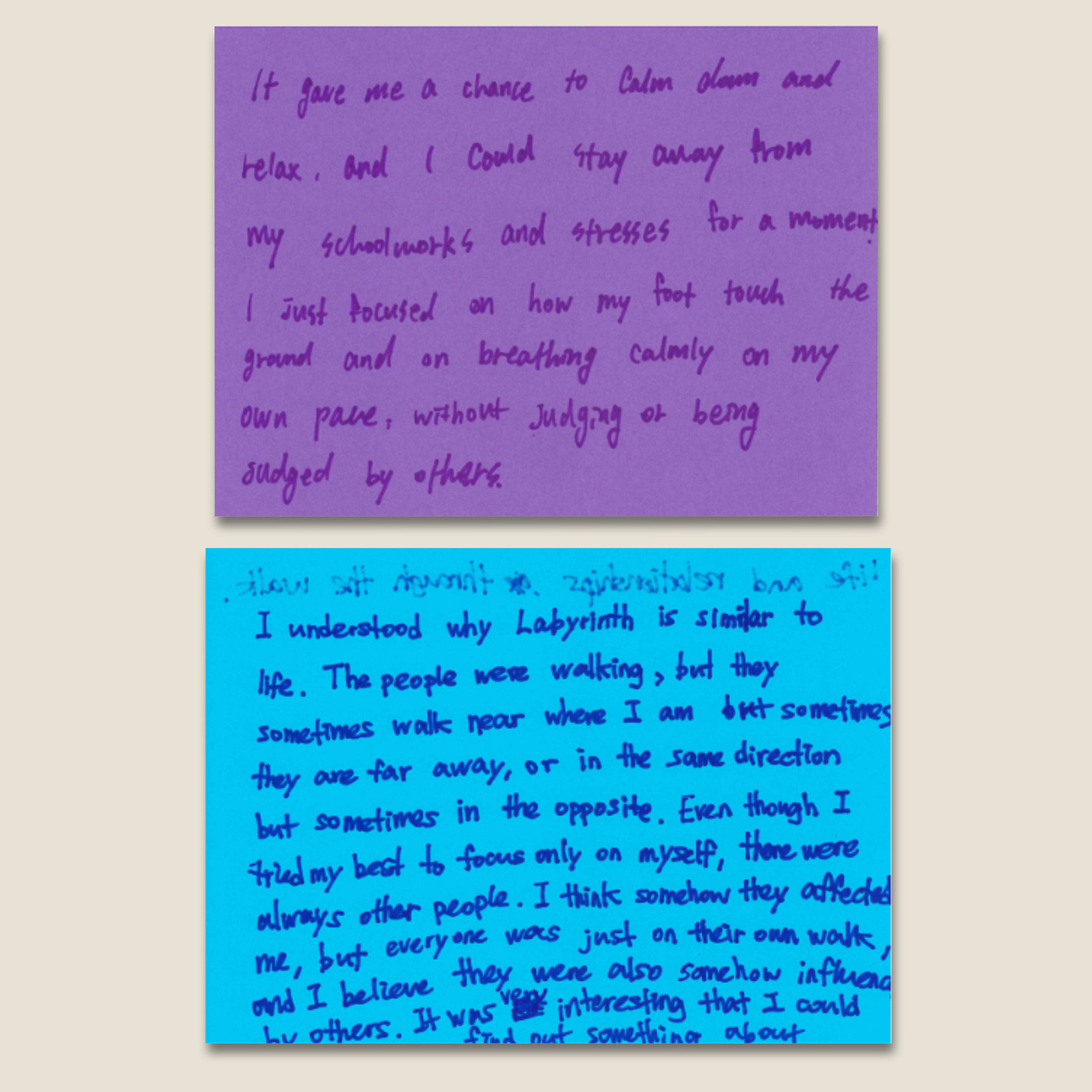

Once they stepped off the tarp, each student was asked to find a comfortable place in the auditorium—on the floor, against the wall, on the stage steps—and write an anonymous message on that blank coloured page. Not a summary of their experience, and not something polished. Just a sentence or two they felt moved to offer; a message they wanted to give to the world without needing to sign their name to it.

Each collected a coloured marker from the writing station where we’d laid out coloured markers in simple piles and found their writing spot. The room settled into the stillness of people choosing words carefully.

Some students wrote quickly, as if the message had been waiting inside them the whole time. Others stared at the page for a long while, chewing the inside of a cheek, testing phrases silently, crossing out and starting again. A few held their paper close to their chest while they wrote—not to hide it from others so much as to keep it private until it was ready to exist on its own terms apart from them.

The path extended outward to here—into the ordinary, vulnerable act of putting words on paper and offering them away.

They had entered the room to receive a message. They left the path having written one.

A few of those precious pages are included below.

Closing Circle

On a labyrinth—whether you are young or old—you begin to feel part of a tide governed by the path itself.

A few of my guests finished writing on their coloured pages early, and I was intrigued to watch them drift back toward the tarp. Without asking permission, without checking what was “supposed” to happen next, they stepped onto the path again. It felt sacred: a second walk chosen purely of their own accord, as if they wanted to find out whether the turns would feel different now that their hands were empty and their message had been given away.

For one student, the second walk became something else entirely. I watched her shuffle forward, then try twirling—circling—and then, unmistakably, dancing. Not for attention. Not for approval. Just a body finding its own language for whatever had been stirred.

South Korean high schools are not, in my experience, places where spontaneous self-expression happens without consequence. Conformity exerts a powerful social gravity here—especially among teenagers. And yet this student’s dance didn’t read as a brave act of non-conformity. No one stared. No one laughed. Another student joined in, walking backwards. Nobody seemed to take any notice. In the temporarily liminal space of a dim auditorium—surf and gulls in the air, feet scuffing on tarp, markers scraping thoughtfully on paper—each person was oddly free: free to be themselves for a moment, without needing to judge anyone else, and without feeling judged. A rare freedom indeed in any high school life.

When it felt right—when the energy had begun to settle—I invited everyone to sit in a loose circle on the labyrinth. They came holding their reflections, and I asked them to share anything they wanted.

There was no pressure to speak. Silence counted as participation. A few students shared anyway—not long speeches, just small, clear sentences about what surprised them, what felt difficult, what they hadn’t expected to feel. Their sincerity had that awkward brightness teenagers get when they don’t have a carefully prepared script to hide behind. There was soft laughter too—not the laughter of alienation, but of recognition.

There was no fire in our circle that night, but there may as well have been. For a few minutes, we gathered the way humans have always gathered: around the warmth of a shared experience. Teacher and students. South African and Korean. People who’d lived in Indonesia and Germany, China and the USA. For that brief stretch of time, we were simply one community that held a world of experiences—a brief glimpse of what could be possible for humanity.

Tuesday, 20 May 2025, 19:00—that bell rang. Nothing lasts forever, and knowing what to release—and when—can be one of the hardest lessons to learn. Thankfully, in schools, that awful bell makes it a bit simpler.

Our time was up. One by one, they entrusted their reflection pages to me, put their shoes back on, exchanged a few words, and made their way toward their classrooms. Some walked hand in hand. Others with an arm around a friend’s shoulders.

A small group stayed behind without being asked. They capped markers, gathered stray booklets and scraps of paper, and began resetting the room.

As the auditorium emptied, the labyrinth was still what it had always been: black tape on a massive tarp. And yet it didn’t feel like just a sum of its parts. Two students helped me fold and roll it. Another two dragged the nets back into place and unplugged my little speaker and iPad—undoing the evenings earlier transformation with the same quiet competence they’d shown while cleaning their classrooms. The auditorium returned to its default identity: gym, stage, multipurpose room.

But the atmosphere didn’t reset as neatly as the furniture.

I turned off the lights and stepped into the corridor. The school had snapped back into its normal schedule. The same D major tune that had poured students into the corridors at 15:50 had now gathered them back into the stillness of their brightly lit rooms full of bowed heads and open books.

And yet, as I started down the stairwells—those flights that double back on themselves—and along the corridors that wind toward the main entrance and the open, warm evening air beyond, it struck me how the architecture of a day is its own kind of labyrinth, whether we notice it or not. We move along a path: the same route in, the same route out, never quite the same experience twice. Every moment of every day asks the same quiet questions of us:

what do you carry,

what do you release,

and what message do you leave on the hearts of others?

I had gone in thinking that I was offering my students an experience. I went in hoping they would get something out of it.

I walked out thinking: maybe we did.

Epilogue

For two months, the labyrinth lay rolled, folded, and tucked away in its expandable luggage bag behind a stack of chairs and a curtain in the auditorium. But that first walk—like all labyrinth walks—extended forward.

On 17 July 2025, during our school’s Major Language Day (전공어의 날), a handful of the students who had walked in May volunteered to return—not as participants this time, but as a small team of facilitators. They could have been out with their friends in the bright chaos of the day—activity booths, games, international snacks, the whole carnival of it—but instead they chose the auditorium again.

The labyrinth went down on the floor once more. This time there were five hundred chairs. We moved them. Then, when the walk was done, we set them back. The nets were dragged. The room was negotiated—again—into unfamiliarity.

Along the perimeter of the tarp, I’d turned the badminton nets into an improvised display: reflection pages hanging like prayer flags, bright sheets of paper carrying words that no longer belonged to any one person.

Many of the students who had walked before returned. None of them searched through the affirmation cards to find the one that had been “theirs.” Almost all of them began on the outside, circling slowly, reading what had been left behind. And every now and then, one of them would stop.

You could see it when it happened. A pause. A tiny shift in the face. A moment of recognition. Those were their words—though nobody else would know it. They knew it. And when another student lingered to read that same message—when those words were allowed to hang in someone else’s mind for a moment—the original exchange completed itself again.

We are shaped, of course, by what happens to us, and by what we’re told. But what defines us—slowly, quietly, over time—is what we choose to do with it. The marks we leave behind. The tone our presence leaves in a room after we’ve walked out of it.

If you made it all the way to the end of this long piece, I’d love to hear from you.

Additionally, if you’d like to catch a glimpse of the kind of stuff we cover in my after-school program, consider checking out my podcast, The Inward Sea, via my Podcast Hub here on Substack.

The finale to Tchaikovsky’s 1812 overture is, I have discovered, in E-flat major—a small but important half-step up from our D major misery.

It is a well established fact that Sports departments all over the world are incapable of recognizing irony, even when it’s bolted to their own equipment.

It made me cry to read this. Thanks for sharing, what a powerful experience.

Thank you for this Dimitri. There is a labyrinth on the land where I live and I have walked it many times. Yet I learned so much from this essay. How lucky your students are to have you as a teacher!