도(스)토리—Acorn Theory & Theseus' Road to Athens

A Labyrinth Walk

16:00–24 November 2025

The final bell rang. Students rushed out of their classrooms to grab a few minutes of break before the evening “self-study” (야자1) period commenced.

For most high school students in South Korea, the formal academic day begins somewhere around 8am, and ends close to 9 or 10pm. After that they often end up going to late-night (and illegal) cram-schools called Hagwons (학원) whose windows are facades made to look as though the institute has closed at 10pm, as per the law, behind which classes continue late into the night.

During the first hour of “self-study”, the school at which I work allows students to enrol in extracurricular courses offered by the teachers. Extra language courses, mathematics and science courses are all on offer—most of which are aimed at topics like how to read exam passages more effectively, or tricks and tips for solving examination problems quickly.

Among these noble and highly practical courses is the occasional oddball: a class aimed at creative story-telling using tarot cards, a course about fairytales from around the world, or, as was the case this semester, one going by the academically dubious title of Mythology and Psychology: The Myth of Theseus. It’s usually my name attached to these. I suppose I take the idea of self-study quite literally.

The date was the 24th of November, in the middle of my final practical assessments for the year and with the final exams looming on the (very near) horizon, I hurried off to the library where I would be hosting the first part of the evening’s special event.

The event took place in two sessions, a classroom session, held in the library during our regular class time, and a second session in the school auditorium which took place in the hour after the students had eaten dinner (our school provides hot lunches and dinners for the students.)

During the first session we reflected on Theseus’ journey to Athens and explored the question When did Theseus become a hero?

Was it when he confronted Periphetes and claimed the bandit’s bronze club?

Was it when he faced Sínis, the Binder, and refused to be bound to the opposing forces of this outlaw’s twin pines?

Was it, perhaps, when he faced and subdued the wild instinctual force of the Crommyonian Sow and her grey mistress, Phaea?

Or perhaps when he faced the false authority of Skíron on the cliffs of Mégara?

Was it when he defeated Cercyon of Eleusis in a wrestling match by using tactics of speed and cunning rather than trying to match the man in strength?

Or did he become a hero when he refused to be fitted to the bed of Procoustes who would either chop off the parts of his victims that would not fit on the bed he offered or stretch them until their joints popped out and they were finally tall enough for his liking.

So, when did Theseus become a hero? And when do we find ourselves equal to the calling we feel for our lives?

The Shameless Plug

If you’d like to walk this path with me and my students, you can check out the links connected to the bandit’s names above for the transcripts of my podcast episodes based on these classes. Or you can search your favorite podcast platform for “The Inward Sea”.

Here are some links, if you’d like:

Apple | Amazon | Spotify | Podchaser | Youtube

Acorn Theory

This is where the Acorn Theory so beautifully taught by James Hillman came in. The Korean word for acorn is 도토리 (DoToRi). And with the help of some beautiful time-lapse videos from YouTube, we explored how the acorn, small though it may seem, holds the genetic material of the giant oak—of many generations of such oaks.

According to Hillman:

…we need to make clear that today’s main paradigm for understanding a human life, the interplay of genetics and environment, omits something essential—the particularity you feel to be you. By accepting the idea that I am the effect of a subtle buffeting between hereditary and societal forces, I reduce myself to a result. The more my life is accounted for by what already occurred in my chromosomes, by what my parents did or didn’t do, and by my early years now long past, the more my biography is the story of a victim. I am living a plot written by my genetic code, ancestral heredity, traumatic occasions, parental unconsciousness, societal accidents. (Hillman, 2017, Ch.1)

In sharp contrast to most modern theories, the Acorn Theory proposes a different point of view, one that holds the redemptive power of a myth told by Plato in his Myth of Er at its heart. In introducing the Acorn Theory Hillman writes:

The acorn theory proposes and I will bring evidence for the claim that you and I and every single person is born with a defining image. Individuality resides in a formal cause—to use old philosophical language going back to Aristotle. We each embody our own idea, in the language of Plato and Plotinus. And this form, this idea, this image does not tolerate too much straying. The theory also attributes to this innate image an angelic or daimonic intention, as if it were a spark of consciousness; and, moreover, holds that it has our interest at heart because it chose us for its reasons. (Hillman, 2017, Ch.1)

Acorn Theory asks us to accept one another and ourselves as beings who come into this world with an image of selfhood—the innate image or diamon—that guides our growth. Like the acorn contains the genetic material that shapes the growth of the tree and all trees after it, our souls contain the code that shapes our lives. When denied, our growth is stunted and maladaptive behaviours and pain ensue.

The acorn theory provides a psychology of childhood. It affirms the child’s inherent uniqueness and destiny, which means first of all that the clinical data of dysfunction belong in some way to that uniqueness and destiny. Psychopathologies are as authentic as the child itself, not secondary, contingent. Given with the child, even given to the child, the clinical data are part of its gift. This means that each child is a gifted child, filled with data of all sorts, gifts peculiar to that child which show themselves in peculiar ways, often maladaptive and causing pain. So this book is about children, offering a way to regard them differently, to enter their imaginations, and to discover in their pathologies what their daimon might be indicating and what their destiny might want. (Hillman, 2017, Ch.1)

So, when did Theseus become a hero? The answer is simply “When he became Theseus.”

And, when do we find ourselves equal to the calling we feel for our lives?

Well…

We already are.

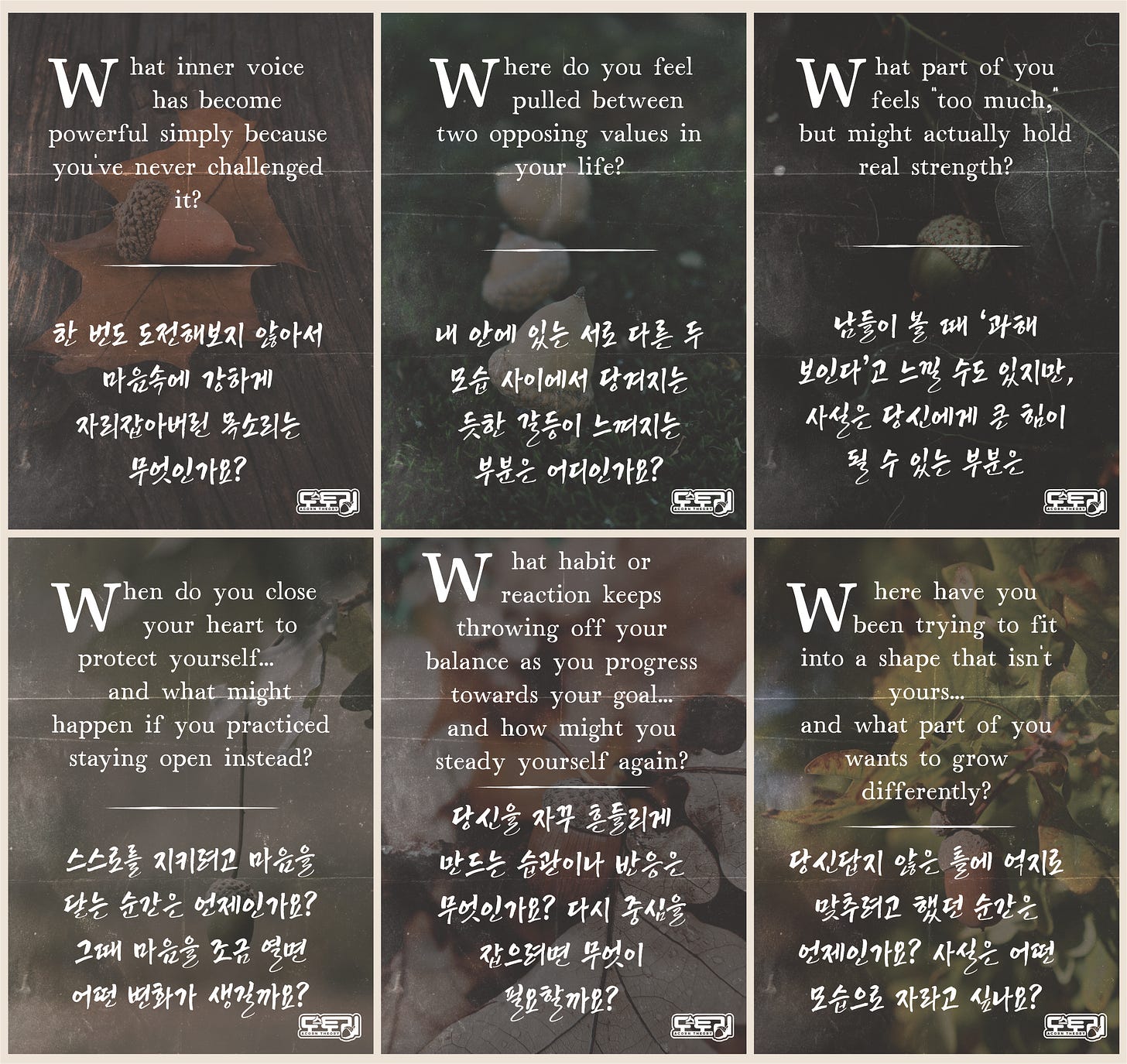

With all of this covered, we returned to the myth of Theseus and asked ourselves a few questions in preparation for the walk.

The students were encouraged to think about these questions and pick one that they felt resonated most with them. No need to share the question, no need to answer it, just take it with them to dinner, and then, after dinner, into the labyrinth.

And with that, the class adjourned. My bright-eyed students hurried off to eat their dinner, and I went to the school hall to move badminton nets and set up the labyrinth.

The Labyrinth

The labyrinth is an ancient archetypal pattern. It pops up all over the world with some of the oldest being ones in northern Russia dating from about four or five thousand years ago.

It appears all around the Mediterranean, in Asia, in the Americas. It is part of pre-Christian cultural practices and can be found on the floors of cathedrals. It seems to be a physical archetype, something that springs from the psyche of humanity.

A labyrinth is not a maze. It is not a puzzle. There are no dead-ends no way to get lost on it (provided you manage not to accidentally step over boundaries of the path). All a labyrinth requires of a walker is that the walker trust the path

This was the third formal labyrinth walk I hosted after completing my facilitation training with the Reverend Dr. Lauren Artress and Veriditas in March of 2025. There are a few labyrinths around South Korea, but sadly none near enough for me to use as part of an experiential learning activity with my students. So, I made one.

For a few weeks, I was hunting on South Korea’s online shopping portals for a large enough piece of fabric. Since I know nothing about sewing, I thought it would be good to find something durable and easy to store. A tarp!

What you might not know about me is that I am horrible at maths. It’s not that I can’t do it. I am sure, if I had applied myself more as a student, I would have loved it… but unfortunately I have one of those math-phobia things. Anyway, imagine my joy when I found a tarp that would… *gasp*… only weigh 1.5kgs and have a surface area large enough on which to create a 5-circuit medieval labyrinth!

You better believe I hit “buy” immediately.

Of course, when it arrived, it was 15kgs of tarp, not 1.5kgs. Luckily, I had help and, armed with permanent markers, lots of string, an old mic-stand, and kilometres of black duct-tape, we crafted a labyrinth. It is 10mx10m and took two weekends of time on our hands and knees to create.

I am happy to report that this tape-n-tarp labyrinth has stood the test of time, now. It has survived hundreds of feet and some very enthusiastic rolling and insistent crushing, and seems no worse for wear.

This was the labyrinth I had to set up for the walk.

The Walk

Towards the end of their dinner time, students started coming in to the auditorium. They helped pull the huge labyrinth a bit smoother and explored it, walking around it, jumping over the “walls” between the circuits of the path, and warming the space with their curiosity and enthusiasm.

Once everyone had arrived, I gave a brief introduction of how to walk the labyrinth. I reminded them that for the duration of this walk, this time and this space was entirely theirs. The only two rules I asked them to observe while walking were:

to remember that they were not walking alone and to make sure that each would allow others to walk with the same freedom from judgment and expectation that they would like to experience during their walk.

to walk in mindful silence, listening to the sounds of their feet on the path.

Everything else was up to each of them. When walking a labyrinth, you can walk quickly or slowly, forwards, backwards, twirling, or skipping. You can crawl if you want. This is your labyrinth.

This is your path.

This is your life.

And, in the center, when they finally reached it, there would something only for them. Something with their name written on it.

We began by walking around the circumference, pausing briefing at 6 stations along the way to reflect on the question posted at it. These were the same questions we had contemplated earlier during class. This time, they were printed on paper small enough for each student to take one that they wanted to walk with—not answer, just walk with, to see what might emerge.

One by one, the students, when they each felt ready approached me at the entrance to the labyrinth and began their walks.

The Center

In the center of the labyrinth there was a small, grey box, and in the box were small black pouches with a tiny wooden acorn pendant in each of them. I wanted to students to have something to remember the walk by and to keep with them through the exhausting three weeks leading up to the final exams. There was also a blank page on which they could write a letter to themselves to record their thoughts and experiences in the walk.

A few of them shared their letters with me after the event. They are incredibly precious and honest windows into the hearts of these wonderful young people.

The Journey Back

The walking and journalling continued for about 45 minutes. Some students returned to the labyrinth for a second walk. After our walk was over, we all gathered on the labyrinth. The path we had just walked became the place where we planted ourselves and felt a sense of togetherness.

We spoke about the name of our walk: 도(스)토리 (Do-S-To-Ri)

While 도토리 means “acorn” in Korean, the Hanja2 character 道 (Dao) is also pronounced 도 in Korean. Our journey with Theseus, our labyrinth walk, and our pondering of the acorn have all been an exploration of the narratives we construct about ourselves: stories (스토리). So, as much as this walk has been about an experience on the labyrinth as part of an extra-curricular course, it has also been about the story of the path, the 道 (Dao) or 도 that each of us walk in life.

It was then that I asked them to look at their acorns.

You see, these acorns unscrew. The tops come off and inside, I had written a note for each of my students. As a teacher, so much of my job is correcting student’s sentences or highlighting where they have made a mistake because the South Korean education system demands a bell-curve for every assessment.

I don’t get to acknowledge effort and growth the way I want to. I have to hold every courageous act of individual effort up against a standard that will yield results that the education system will acknowledge. I have to play an unwilling role in a machine that ranks and (perhaps inadvertently) dictates so much of what these teens feel is their personal worth and potential through scores. So, when an opportunity presents itself, I want to make sure that they know that they are worth so much more.

For each kid I had written a short comment about something admirable I had noticed in them this semester.

There were tears. I had to try hold back a few of my own.

Whatever happens to those little acorns, I hope the memory of what they mean will stay with those who walked. I know it will with me.

The End

The bell rang. My students had 10 minutes of break time before they had to return to their classrooms and begin studying, but most of them were concerned about how I was going to roll up the labyrinth alone.

I’ve done it before. It takes about an hour to do it well enough to get it back into it’s bag.

Perhaps they are just nice kids. Maybe it was a shared sense of community and camaraderie focussed on what we had just experienced together. Or it may have been that they simply didn’t want head back into their classrooms where their books and the threat of scores were looming over them, but whatever it was, I was very grateful that everyone wanted to help roll the labyrinth.

There was running and laughing as they helped drag the corners from one side to meet those at the other—like folding a giant blanket. The labyrinth billowed like the sails of a great ship, reminding me of how this static pattern of concentric rings is a vessel of exploration capable of carrying us to incredible new worlds within ourselves.

This time, it took just 10 minutes, and the labyrinth was back in its black expandable luggage carrier, tucked away behind a curtain in the hall.

We turned the lights off, and went out into the night.

Sources

Hillman, J. (2017). The soul’s code : in search of character and calling. Ballantine Books.

야자 is the informal shortening of the Korean 야간자율학습 which is the time when when most Korean high school students stay at school after the academic day has ended and study in their classrooms. The school is manned by a skeleton crew of one or two teachers who patrol the corridors (or hide in the their office drinking coffee) while students hit the books.

Chinese characters in Korean.

اتعلم من كتاباتك حول السرد

You are such a passionate teacher! I hope you don’t ever loose that fire in your belly. We need more teachers like you! So thoughtful and clearly making an impact on these young adults

I cannot believe what long school days these kids have! It sounds more like a prison of sorts! Do they get long breaks and to play sport ?

It’s good that you teach a subject where you can get creative with them in your delivery and make it interactive and fun! Humans learn best when playing!